How to Create Personas Without Losing the Person-ness

Elyse Kamibayashi, Former Senior Brand Strategist

Article Categories:

Posted on

Personas just want a fair chance.

There’s nothing like discovering you’ve been a snob about something that's actually pretty great.

I’m referring to audience personas (also known as audience archetypes) — which, up until a year ago, I greatly enjoyed looking down upon. Based on limited experience, I thought they were superficial and unhelpful — a waste of time for brands that needed to know more about their audience than how much money they made.

As it turns out, personas (like so many other things) are only as good or as bad as we make them. We’ve become used to a type of persona that only tells us what our audience does for a living, how much they make, and what kinds of newspapers they read. We’re not used to seeing personas that get into the weird, complicated reasons behind a person’s choices — why they read those kinds of newspapers, why they love their job, or why they don't love their job. We’re not used to seeing personas that deal with the whys. But that doesn’t mean they can’t.

Wondrium

View our workWhen we worked with The Great Courses on rebranding and redesigning their flagship streaming service, The Great Courses Plus (now called Wondrium), we used personas to explore one question: why did our audience want to learn? The process was harder and stranger than you would ever think persona work could be, but it yielded insights that helped us understand the people we were trying so hard to reach. And because of that, we were able to reach them in ways we never expected.

So, how did we go about creating personas that kept their person-ness?

Step 1: Organize the “what” before you try to find the "why"

This step might also be called, “patience, grasshopper.”

We were lucky that our client team had been extremely diligent about compiling data on their audience’s behavior, and gathering feedback from them directly through surveys and focus groups. We had access to a mountain of data, and all I wanted to do was take my vorpal sword in hand and start slashing around for core motivations. It does not, of course, work that way. Thankfully, the UX designer on our team took a more prudent approach, suggesting that we first organize and distill the information we had, so we would at least know where to start digging.

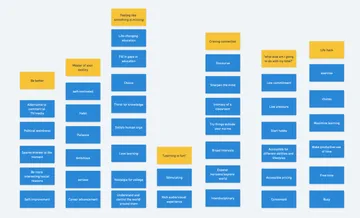

This meant spending two weeks studying every graph and reading hundreds of survey responses. We then looked for patterns in the ways that people described learning, drawing out key words and key phrases. We coded giant Airtables full of data, until at the end, we were able to draw out a list of the most common words and expressions people used to describe why they loved learning.

We then grouped them into like categories, until we had seven columns of cards referring to things like "political weirdness," "understand and control the world around them," and "low pressure."

Then and only then did we start to think about what on earth all of this meant.

Step 2. Question everything

We now had a clear, defined place to start thinking about why, deep down, our audience loved learning. This next step involved leaving the world of analyzing, categorizing, and organizing, and making the ungainly leap into wondering. We sat back, looked at the cards, and started asking simple questions like: why would someone want to have an alternative to commercial TV and media? Why would they want to use a course on bread-making to escape from politics?

We didn’t ask terribly intelligent questions — we were, however, willing to follow those questions as far as we could possibly go, and then a bit further.

I should mention that, at this stage, it’s extremely helpful to be within shoulder-tapping or at least yelling distance of your teammates (Slacking works in a pinch). You can use exercises like the five whys to get to the bottom of your audience’s behavior, but I tend to believe that discussing and debating the research (when you do it fearlessly and rigorously), gets better results.

Our first round of collective wondering allowed us to identify a core motivation within each column.

For example: the first column boiled down to a desire to just be better — be better than watching Netflix all day or getting embroiled in political debates — and, perhaps (if they're being honest) try to be a little smarter than the other people in the room.

After another round of discussion, we eliminated the categories that were seen less frequently in the research, and refined the existing motivations again, landing on a final set:

At this point, we could say that much of our audience loved learning because they wanted to connect with the world. Or they wanted to engage in self-improvement. Or they were just inexplicably drawn to learning and couldn’t articulate why.

We had some fairly solid “whys” — some core motivations that could explain our audience’s behavior and the way they talked about learning.

The question was: what then?

Step 3: Figure out what to do with your "whys"

Technically, we could have presented that list of motivations to our client team without anything else. Going from mountains of raw data to a set of seven core motivations felt like a win to us in the moment — but it wasn’t enough.

We wanted our client team to actually use what we found as they continued to get to know their audience. And lists, though temporarily useful, can be forgettable in the long term.

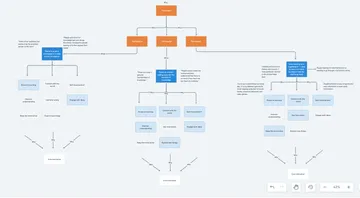

Plus, there was another twist: Our client team had already identified two high-level personas for their audiences. They called them Seekers and Solvers. Seekers were described as people who loved learning for the sake of learning, while Solvers generally had something in mind that they wanted to apply their knowledge to. We weren’t obligated to use those personas, but our research didn’t disprove them. In fact, it proved that they were a valid way to group our audience at a high level.

We decided to build on the existing structure by keeping Seekers and Solvers, but treating each of them as a “family” of personas, and creating more specific personas based on our research.

Our decision to use personas as the vessel for our “whys” was not just because they’re a handy way to organize information. It was because 1) we knew they would be a familiar tool for our client team — something they could use without having to waste time adjusting to something new — and 2) because we wanted to make our audience feel as human as possible. Personas can remind us to think about our audience as people, rather than data.

Step 4: Build your humans out of the "whys"

The first thing we had to acknowledge was that our audience likely did not have just one motivation for learning. They would be driven by a weird combination of the motivations we had landed on. There would be areas of overlap, and in that overlap lay something even more nuanced and human than what could be found on the initial set of seven cards.

And this brings us to one of the main benefits of persona work. Done well, it can force you to embrace the glorious messiness and complexity of the humans in your audience. Rather than trying to herd your audience into neat boxes, it can make you adapt your boxes to your humans.

We started putting together different combinations of motivations, and wondering about the kind of person that emerged. We saw a lot of people who combined the inexplicable urge to learn with a desire to engage with ideas. We saw that these people often didn’t think as much about self improvement. These people were perhaps the most idealistic, if not always the most practical or consistent. A quixotic person started to take shape the more we thought about it — and thus “The Quester” (proud member of the Seeker family) was born.

The rest came along in much the same way. We looked at groupings of motivations, then stepped back and wondered: “what kind of a person thinks like that?”For each one, we asked: does this feel like a real person with real hopes, frustrations, and aspirations — all of which could prompt them to turn on a course about the Ancient Olympics, or painting, or the Pirate Wars of 1718?

Our final personas were:

Seeker Family:

The Collector — A person who enjoys "collecting" as much information as they can, and using that information to weave complex "information tapestries" that help explain the world around them.

The Quester — A person who sees learning as a lifelong journey that is inherently good and noble.

The Snacker — A person who uses learning to enhance everyday activities. They may not "need" to learn, but that doesn't mean they can't enjoy it.

Solver Family:

The Supplementalist — A person who wants more in-depth information on a subject they're studying (example: a student trying to do extra well in a class). They believe that having the right information comes from having all the information.

The Late Bloomer — A person who may not have had much free time to explore their interests in the past, and who now sees learning as a way to do something fulfilling with their free time (while still being responsible).

The Artisan — A person who longs to connect with someone (an expert) who can help them become better at an activity they enjoy.

In writing the description for each persona, we had the chance to go even deeper into our audience’s motivations — to the point where the set of seven that we started with began to feel more like “interests” rather than core drivers.

We bolstered the write-ups with audience quotes, and ended with a description of the challenges and opportunities that would be involved with trying to reach any of these personas.

In conclusion

I stand corrected. I’d like to offer a formal apology to all the personas I’ve snubbed in the past. There’s more to them than meets the eye.

Personas can help us make well-informed hypotheses about our audience. They can help us understand each segment of our audience on a deeper level. They can do a lot of things. Whether or not they actually do depends on us. If we decide that our personas should be a nice, tidy set of stats, then they will be happy to oblige. If we want them to be a tool for understanding the complexities of our audience’s needs, hopes, and dreams, then that is exactly what they can be.

Like the people they describe, personas are not perfect. But, if we let them, they can help us approach our audience with patience, curiosity, and compassion — things no brand should be without.

NB: These personas would not have been possible without the help of three very brilliant persons. Huge thanks to Senior UX Designer Katherine Olvera, Creative Director Ally Fouts, and Art Director Elliott Muñoz.