Using GitHub for User Acceptance Testing with Clients

Ryan Schaefer, Former Senior Project Manager

Article Categories:

Posted on

User Acceptance Testing is an important part of any product launch. It will result in a nicely polished product and is vital for catching unknown bugs. Make it a part of your game plan.

Picture this: Your development team has just wrapped up their last ticket for the very last weekly sprint. The beautiful comps your design team put together are now fully realized and working in the browser or app. Things have been going great. Now the client wants to see how everything works together in concert.

What’s next?

Typically, that’s User Acceptance Testing (UAT). UAT can be a significant part of any product launch. The main goal is to verify that the product works as intended.

UAT can take many different forms, and vary in the amount of people brought in as users. It could be an ongoing process broken down into discrete features, components, or templates. Or it could be batched all together near the tail-end of development.

For a major, highly anticipated product, UAT often takes shape as a private or public beta in which the intended audience are the everyday users. For smaller launches, it can be sufficient to rely on internal project teams to carry the load. Often, the decision for how many people to involve in this part of the project rests on the client and depends on budget, team availability, and product complexity.

Below, I’ve outlined a methodology that’s proven effective for managing UAT with a client team.

Plan for it up front.

While you’re setting up milestones, make sure to build in at least a week for dedicated UAT time. A vital part of software development is QA — it needs to be given the proper attention and planned for accordingly. The exact amount of time spent will depend on the size of the testing team and the size of your development team. This doesn’t include ongoing functional QA (essentially, a rolling process during which your designers, UXers, PMs, or dedicated QA team take a first pass at each page or component as it’s deployed). This should be consistent and start as soon as possible.

Utilize feature definition.

Feature definition serves many purposes, but, in addition to signalling to developers how something is expected to behave, this documentation can also be used as a guide for your testers. Following a user journey, if that’s the way you’ve broken it down, is not a complicated process and shouldn’t be too arduous for less familiar users.

There are a lot of ways to track this step in the process: via spreadsheet, Airtable, Trello, or basically anywhere you can share records and track progress. Ideally, these behaviors should already have been agreed upon and approved, so nobody encounters anything surprising and can treat this as the source of truth for testing.

Establish a process for communicating feedback

Whatever your preference, make sure to cement it with your client. The worst case scenario is you’re receiving reports in multiple places. That’s how things slip through the cracks.

My preference and recommendation is to use GitHub issues. It meets all the necessary criteria, is visual, and is likely the canonical place where you’re developing anyways. If you go this route, there are some standard things you can do to streamline the process.

Set up a project board with the client.

GitHub provides a built-in feature for projects. Another tool that serves a similar purpose with some slight variations is Zenhub. There are more out there, but you’re generally looking at the same suite of capabilities for any of them.

Add your pipelines.

Here’s how I have been breaking it down lately for client-facing boards:

- Viget-found Bugs: This is for anything you surface during internal testing that hasn’t already been addressed. It’s important to note these so the client isn’t wasting their time calling out something you’re already aware of.

- Client-found Bugs: This is the primary client space. All bugs found should be logged here.

- Feature Requests: Everything that isn’t an explicit bug goes here for discussions on feasibility and clarification (more info on distinguishing this from a bug report below).

- In Progress: Anything that is actively being worked on gets moved here. This keeps the client abreast of progress in real-time.

- Ready for Client QA: After a bug report has become actionable, fixed, and deployed, tickets should be moved here and re-assigned.

- Backlog: This space should be composed primarily of feature requests that are not strictly within scope, budget, and timeline. Not all feature requests go here — only the ones your team won’t be able to get to. It’s important to set the expectation beforehand that not every ticket filed can be addressed.

- Approved by Client: Once the client approves a fix, they should close the ticket. Set up an automation so that tickets are added here when they’re closed.

Clearly define a bug vs. a feature enhancement.

Sometimes it can be hard for testers to distinguish between a bug and a feature request. A bug is when something doesn’t work—when something is explicitly broken. Some examples include:

- A database or server error occurs when you initiate an action or go to a page

- A URL that is expected to load shows a 404 error

- When you click to advance a carousel, the carousel does not advance as expected

- A video does not load as expected

- Clicking a toggle button does not toggle the UI as expected

- Spacing, fonts, colors, or UI elements are clearly incorrect

A feature request is a new functionality, animation, or anything on top of what was already designed and planned for. Some examples include:

- Changing character limits on any field

- Making a non-admin manageable field editable in the CMS

- Rejiggering of any UI elements

- Any and all added functionality

Almost always, bugs should be prioritized over feature requests. Feature requests should be de facto backlog items and addressed during extra time within budget.

Set up ticket templates.

This will make your life much easier. Having a few ticket templates set up ensures you get all the necessary information for your developers to replicate and debug.

An added bonus: the amount of information they’re asked to log ensures they’re testing thoroughly. For example, a user may be looking at something in one browser and want to log it as a cross-browser issue. But if they’re forced to log specific browser info, it encourages them to look at another to make sure it’s not specific to just one. This helps the developers address the issue more quickly.

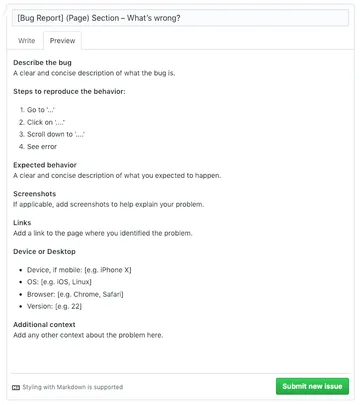

Here’s bug report template I’ve found to be effective:

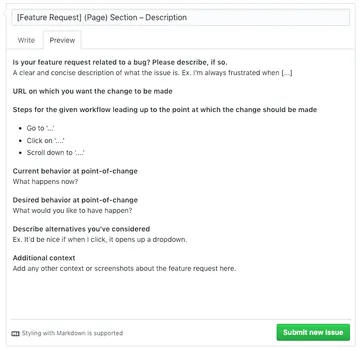

And here’s a feature request template that’s worked for me:

Include labels.

This helps provide context for the entire team. The quantity and granularity can vary, but you should try not to overload the tester with too many. Here are some options for effective labels:

- Bug

- Feature Request

- Page

- Showstopper

- High-priority

- Low-priority

- Estimate: # of hours

- Blocked

- Question

- Duplicate

- Launch Day Task

- Failed QA

- Passed QA

Clearly delineate responsibilities for every ticket (yours or your client’s).

Oftentimes, this is apparent. If a client is filing a bug, it’s now on your team to make it actionable. This is also where the “Question” and “Blocked” label come in handy — if your team has a question, it’s on the client to answer it. Assigning and re-assigning users can also be helpful here.

If possible, appoint one client-side person to submit all requests. This helps filter duplicates, and if they’re technical-minded, it’s even better since they should be able to identify development issues from content issues.

Take a daily inventory.

This aims to answer things like, “How did we do today?”, “What does tomorrow look like?”, and “Are we on track for the rest of the project?”.

If you’re already doing daily standups (which I recommend, particularly for more involved projects), consider extending them to have discussions around remaining tickets. You should be looking to label each one as actionable, needs clarification, or feature request, and attaching estimates.

This phase of the project will result in a nicely polished product, and is vital for catching unknown bugs. There will be things your team missed — that’s just how software development goes. Project Managers should set that expectation early. Don’t let it be discouraging, for either your team or the client team. The more preparation and planning you put into this, the better the end product. And that’s what everyone is after.