Hiking Apps & Outdoor Safety: A Critique

Emmi Laakso, Former Senior Product Designer

Article Categories:

Posted on

New hikers are flocking into the backcountry in unprecedented numbers and apps are their tool of choice. Let's take a look at how some of the most downloaded hiking apps help (and hinder) novice outdoor enthusiasts make safe decisions.

While a lot of industries have suffered in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, outdoor recreation has seen a veritable boom. Local newspapers are awash with stories of unprecedented volumes of people, often first-timers, heading into the great outdoors in comparison to previous years, and outdoor retailers have seen exponential growth in demand for gear. All in all, that’s a really great thing; nature has become a much-needed respite from a life centered around staying home and avoiding the usual places people might usually gather to hang out in the “before times.”

Unfortunately, along with a rise in recreation, calls for backcountry rescue have followed suit, with teams in British Columbia, Colorado, Wyoming, and throughout the West experiencing a larger-than-average volume of rescue calls in 2020. While we don’t have great data yet on what has specifically prompted the need for rescue in the past year, data from sources like the National Park Service (NPS) gives us a sense of what likely contributed to these rescue calls. According to the NPS, the most common activity that led to Search and Rescue (SAR) calls from 2003 to 2007 was day hiking, often in mountainous terrain; “Errors in judgment (24%), fatigue and physical conditioning (20%) were identified as contributing factors in all SAR incidents. Insufficient equipment, clothing, and training were factors in 16%; weather conditions such as heat, wind, cold, snow, lightning, and poor visibility were factors in 11%; equipment failure was a factor in 7%; and darkness was a factor in 5%.” These statistics indicate that, historically, at least 50% of rescues were due to, in one way or another, hikers’ inexperience with their own physical limitations, the weather, or important equipment.

Educating newcomers about risk management in the outdoors has long been a challenge; classic channels for safety education have also been largely ones that recreationalists have to opt into, meaning that information rarely reaches the demographic that most often needs rescue; men, ages 20-29. So, what is the best way to reach these folks? It turns out that just as outdoor gear has seen a boom, so have outdoor apps, which offer a convenient way to plan and track hikes and other outdoor adventures. AllTrails alone celebrated over 1 million paid subscribers and over 25 million registered users in January of 2021 (Yahoo). These apps, due to their popularity, arguably have unique access to those who might not otherwise seek out safety education before foraying out on a trail. While safety is ultimately the responsibility of the recreationalists themselves, as both a user experience designer and a search and rescue volunteer, I thought it would be interesting to investigate how some of these most downloaded hiking apps communicate information to help or hinder hikers in making safe decisions.

Fatigue and Physical Conditioning (20%)

Since “fatigue or lack of conditioning” was cited as a leading contributor to rescue calls in the National Parks, it seems appropriate to start by looking at the ways in which outdoor apps clue users into how hard a hike might be. Most hiking apps provide distance, elevation gain, and some sort of a difficulty rating as a standard way to communicate that information. Unfortunately, many difficulty ratings are presented without any explanation, which means they end up being largely subjective.

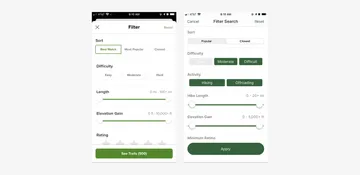

AllTrails on the left, GaiaGPS on the right. What does "Hard" even mean?

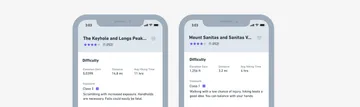

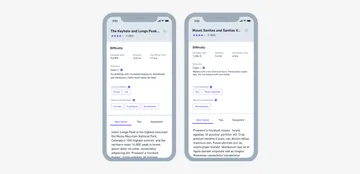

Even apps that do provide some kind of description related to difficulty, like the Hiking Project, are not immune to some of the same issues. For example, both AllTrails and the Hiking Project rate the Keyhole Route on Longs Peak and the Mt. Sanitas Trail in Boulder as “hard/difficult,” but, while the Mt. Sanitas Trail is a 3.2 mile out and back trail to the top of a relatively low elevation peak just west of Boulder, and considered a Class 1 on the Yosemite Decimal System, the Keyhole Route on Longs Peak is a 14+ mile alpine route to the top of a 14,000 ft peak, and includes Class 3 scrambling, with significant risk of a fatal fall.

Longs Peak is on the left, Sanitas is on the right. One of these things is not like the other.

The relative difficulty between those two “hard” hikes is vastly different, and using the same rating for both might lead inexperienced hikers to strike an inaccurate comparison between the two; the idea that if you’ve hiked Mt. Sanitas, maybe Longs Peak isn’t much too different.

To prevent these types of false comparisons, it would be valuable for these apps to establish (or in the case of the Hiking Project enforce) a well-defined and multi-faceted scale that allows for universal comparison between hikes that a person has done in the past and the hike they’re considering. A multifaceted approach could separate out different contributors to difficulty, like overall elevation above sea level, elevation gain, distance, exposure, and even how well graded the trail is.

Even just removing the "hard" rating and instead integrating the Yosemite Decimal System would go a long way in creating some contrast in difficulty for these two hikes.

Weather Conditions (11%)

Weather conditions such as heat, wind, cold, snow, lightning, and poor visibility were factors in 11% of rescue calls, and likely also played a role in rescues related to insufficient equipment or clothing. Of the three apps surveyed, only AllTrails provides a visually prominent low and high temperature for a given day, as well as the weather forecast and sunrise/sunset times, which can help hikers anticipate conditions for their trek.

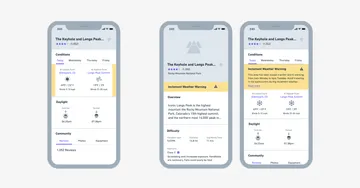

Example of weather information from AllTrails.

That being said, from a safety perspective, this information currently has limited value, and may even be misleading in mountainous terrain because it is focused on a single point rather than the full area that a route goes through; while it may be above freezing and sunny at the trailhead, at elevation a route might be significantly colder, with poor visibility or snow.

For example, according to AllTrails (left), the weather for The Keyhole and Longs Peak via Longs Peak Trail for April 8, 2021 was windy, but with high temperatures at a relatively balmy 50 F. According to Mountain Forecast (right), the high temperature for the top of Longs Peak was entirely different; 19ºF, with 1ºF with windchill. Certainly, anyone who recreates near Longs Peak regularly knows that conditions can be extreme above treeline, but considering at least 67 people have died on the mountain, it’s worth pointing out that this may not be obvious to everyone.

Instead of a single monolithic weather forecast, apps could provide temperature and weather information for both the trailhead and highest point for each hike, especially when the difference in elevation is more than 2000ft, or meets some other preset criteria. They could also highlight inclement weather, like thunderstorms, snow and heat waves to ensure hikers know they are heading into extreme conditions, and perhaps should reconsider.

Super duper rough wireframes to show possible adjustments to temperature display, and notifications around inclement weather.

Insufficient Clothing and Equipment (16%) / Darkness (5%)

Insufficient clothing, equipment, and experience accounted for 16% of rescue calls, and darkness (easily remedied by a light source) accounted for 5%. Aside from unexpected weather or temperature changes as mentioned above, difficult trail conditions such as ice or deep snow without adequate equipment can result in injury or exhaustion. At present, trail conditions and necessary equipment mostly get communicated informally in hiking apps through comments left by members of the community.

Only The Hiking Project has a structured “conditions dial”, which helps show at a glance what hikers can expect trail conditions to be like (as long as others provide timely updates). The app also has a “Need to Know” section, which is often used to surface recommended equipment, though not consistently.

Because this information is currently largely unstructured, there are many ways to improve how it gets presented in apps. For example, apps could create structured tags for equipment, and allow users to upvote the tags they found most useful to bring valuable community-driven content to the top. These could then be surfaced more prominently to help others plan accordingly.

Structuring community-submitted beta a bit could help surface important information about conditions and needed equipment, if it’s available.

To prevent hikers from being caught in the dark, apps could also take note of the time a user starts a hike (since many of them have recording capability), and provide a warning or countdown to darkness to highlight the need for a light source.

Looking to the future.

The Covid-19 pandemic has helped many people rediscover the joys of spending time in nature, and it’s likely that even as life finds a new normal the energy and excitement for the outdoors will continue. That is why it’s more important than ever that we find new ways to reach new recreationalists in the places and apps they already spend time in and provide information that can help them make safer choices. This is just a jumping off point for further ideation and research, but I hope that it serves as inspiration and a reminder that while ultimately hikers are responsible for their own safety, the apps that cater to them also need to consider how they reinforce or hinder safe decision making in the outdoors.