Database Taxonomy

Ben Scofield, Former Viget

Article Category:

Posted on

In my domain modeling/alternative database talk, I usually spend some time talking about taxonomy in biology. It's a fascinating field, with a lot of interesting tangents (ligers and tigons and pluots, oh my!), but in the presentation I focus on how difficult it can be to model in a standard relational schema. I think there's another set of lessons that people interested in databases can draw from taxonomy, however, and that's a way of looking at how databases are related.

Similarity #

There are two main techniques in taxonomy for classifying things. Numerical taxonomy is the practice of grouping by similarity - dogs are more similar to bears than they are to cats, so dogs and bears fall into the same suborder (Carniformia, versus Feliformia for cats).

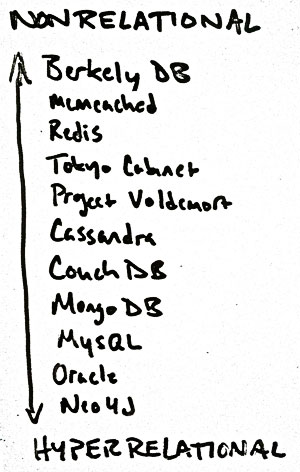

As it turns out, we can group databases by similarity, too. Many lists already do this at a macro level, but they don't do it systematically. I think the right approach here is to identify some axis, and plot the choices along it. Here's an example where the axis is degree of relationality the database provides (with just a subset of databases, of course):

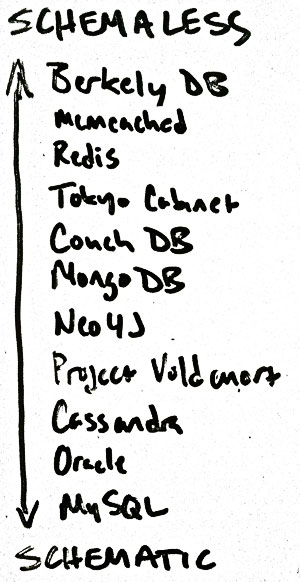

On the other hand, we might also try grouping them based on the degree to which they require data to follow a pre-built schema:

The big changes between the relationality and schema rankings are the move of graph databases (which are schemaless both within individual nodes and for nodes' relationships), the swap of document-oriented and column-oriented databases (which, granted, may just be an opinion), and Oracle's move within relational databases (based mostly on its support for object storage, which is very close to document storage).

Descent #

The other main technique in biological taxonomy is cladistics, where relationships between things are identified based on common evolutionary descent. In other words, humans are more closely related to chimps than to lemurs because the common ancestor of chimps and humans occurred more recently than the common ancestor of humans and lemurs (but I bet that common ancestor was darn cute).

In biology, cladistics presents some obstacles – we can't actually go back in time and see the divergence of species, though we've gotten really good at reconstructing lineages based on rates of mutation and the like. With databases, however, this is a lot easier. Heck, half the time it just takes a quick visit to Wikipedia, or maybe an email to the core team for the application.

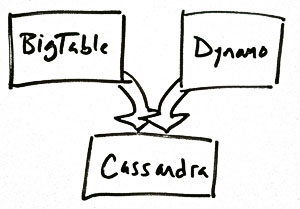

Regardless of how the history is constructed, however, these trees can provide interesting and useful information. For instance, knowing the genealogy of Cassandra gives you an excellent idea of the sorts of situations for which it is designed:

Doing a full cladistic breakdown of the database landscape is beyond the scope of this article (or of any one person with a job, I think), but I welcome comments and suggestions for relationships!